|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Günter Willscheid

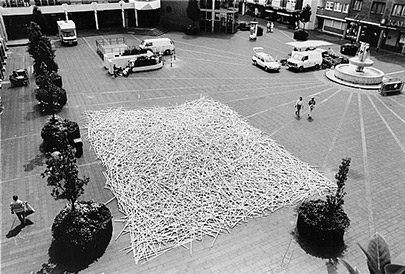

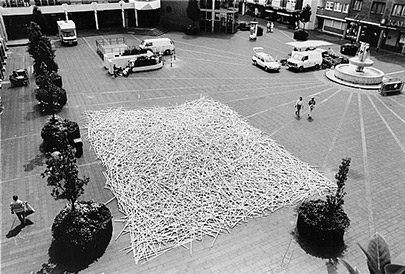

Daniel Zimmermann's measure of all things is 2.70 m long, 2.5 cm wide and 1 cm high, and it turns out to be a customary plasterer’s spruce slat. That's all he needs to put a enchant spaces, and, as he does in Troisdorf, to seemingly play large-scale Mikado with 6 400 wooden slats, to accentuate and defamiliarize situations he happens to find, be they architectural, as on Wilhelm-Hamacher square, or natural, such as at the Sieglar Lake.

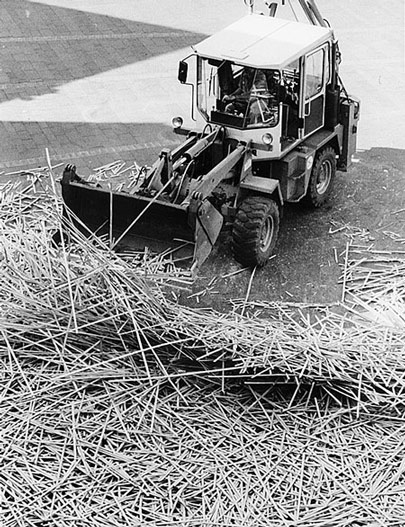

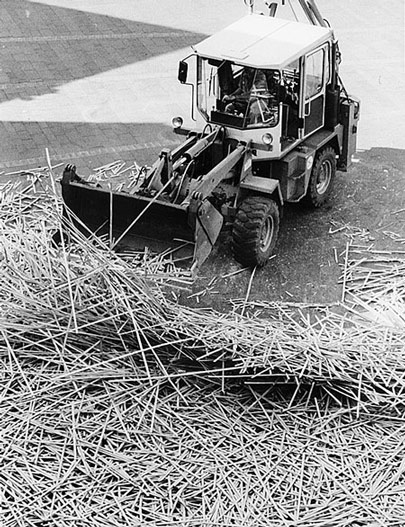

Daniel Zimmermann has created two structural fields, each measuring 12 by 17.5 m, the integration, transformation or dissolution of which he then leaves to their respective environments, be it a city or a landscape. Whereas the structural field at the Sieglar Lake is gradually ensnared and swallowed up by grass, its pendant in the city has long since dispersed. Only two 3D-viewers positioned on-site, which are slightly reminiscent of telescopes, such as those one finds at vantage points to view a touristic highlight, preserve the original condition of both fields, and present a concession to the longing of man to be able to halt time.

Meanwhile Zimmermann fights against "the pretense of immortality", that is being expressed in traditional sculpture. To the contrary, Zimmermann's is a temporal art, sometimes an art just in the moment.

His concept is influenced by many currents of 20th century art. The confinement to simple wooden slats as a means of creation is reminiscent of the Constructivists or Minimal Art, the emotional dealing with it reminds of Action Painting with different means. "In a limited space", the artist states, he provides for "unlimited freedom". Zimmermann creates exciting structures and hatchings, however, extending into the third dimension. He creates "constructures", sometimes in a stringently systematic way, sometimes in a playful way of expression. In Zimmermann's other installations, slats run through entire spaces like spider webs, bundled again into almost classical sculptures again, or turned into props of happenings in his "meeting-slats", which could, and perhaps should, be broken by his interlocutors.

Of course, all these terms, whether they are Action Painting or Happening, are only vaguely appropriate to address the artist's intentions. He at best uses the paradigms of Classical Modern Art to find a way for himself, and thus he's treading along and crosses borders. Sol LeWitt's theory, that an idea can be art in its own right, could prove him to be a conceptual artist, but Zimmermann also offers the implementation of his works, although his actions as a creator do not necessarily need an audience, like the happenings, because they have a lasting effect. The emerging of 'constructures' are but part of the process, which in a way transcends dispersion and leads to a new shape.

He might like the fact that his structural field at the Wilhelm-Harmacher square was dispersed within a matter of days and eventually was used as material by the children of the summer arts school. The choice of material is no accident; as itself inherently symbolizes the dichotomies of "City/Man - Nature/Landscape". Evidently a wooden slat is simultaneously as much a product of nature as it is man-made, and both, a playing child or a gust of wind, partake in shaping the structural field.

Man and nature, as is the artist's wish, actively percolates the discussion, from which his sculptural work emerges day by day anew, or redefines places: That said, it is not least an interactive art, which is informed by both its architectural and natural environment, as by reactions of vegetation, climate and man.Günter Willscheid Art Critic Bonn/Köln